Cybersecurity used to be a numbers game. Count the vulnerabilities, patch the riskiest ones, repeat. Boards measured success by reducing CVE backlogs, security teams measured progress by prioritizing “verified exploited vulnerabilities,” and regulatory frameworks reinforced it. But a growing body of evidence suggests that the foundational assumption behind this strategy of defenders having a reliable view of which vulnerabilities are being exploited is breaking down fast.

The reason isn’t philosophical. It’s architectural.

Modern applications are built on open source. The 2025 Open Source Security and Risk Analysis report shows that 97% of applications include open source components, with roughly 70% of the average codebase originating outside the organization and more than 900 open source components per application. These components accelerate development, but they also multiply exposure with every dependency pulled into a build.

Organizations have long relied on the U.S. Cybersecurity and Infrastructure Security Agency’s Known Exploited Vulnerabilities (KEV) list to illuminate the danger within that complexity. If KEV confirmed a vulnerability was being exploited in the wild, teams could prioritize it over the thousands of others that made headlines but posed no immediate threat.

Miggo Security’s latest research suggests that this logic no longer reflects reality.

The Data That Exposes the Prioritization Illusion

Miggo studied more than 24,000 open-source vulnerabilities from the GitHub Security Advisory (GHSA) database, spanning major code ecosystems such as npm, PyPI, Maven, and RubyGems. Out of those disclosures, Miggo identified 572 vulnerabilities with at least one GitHub-hosted exploit repository, evidence that working exploit code already exists publicly.

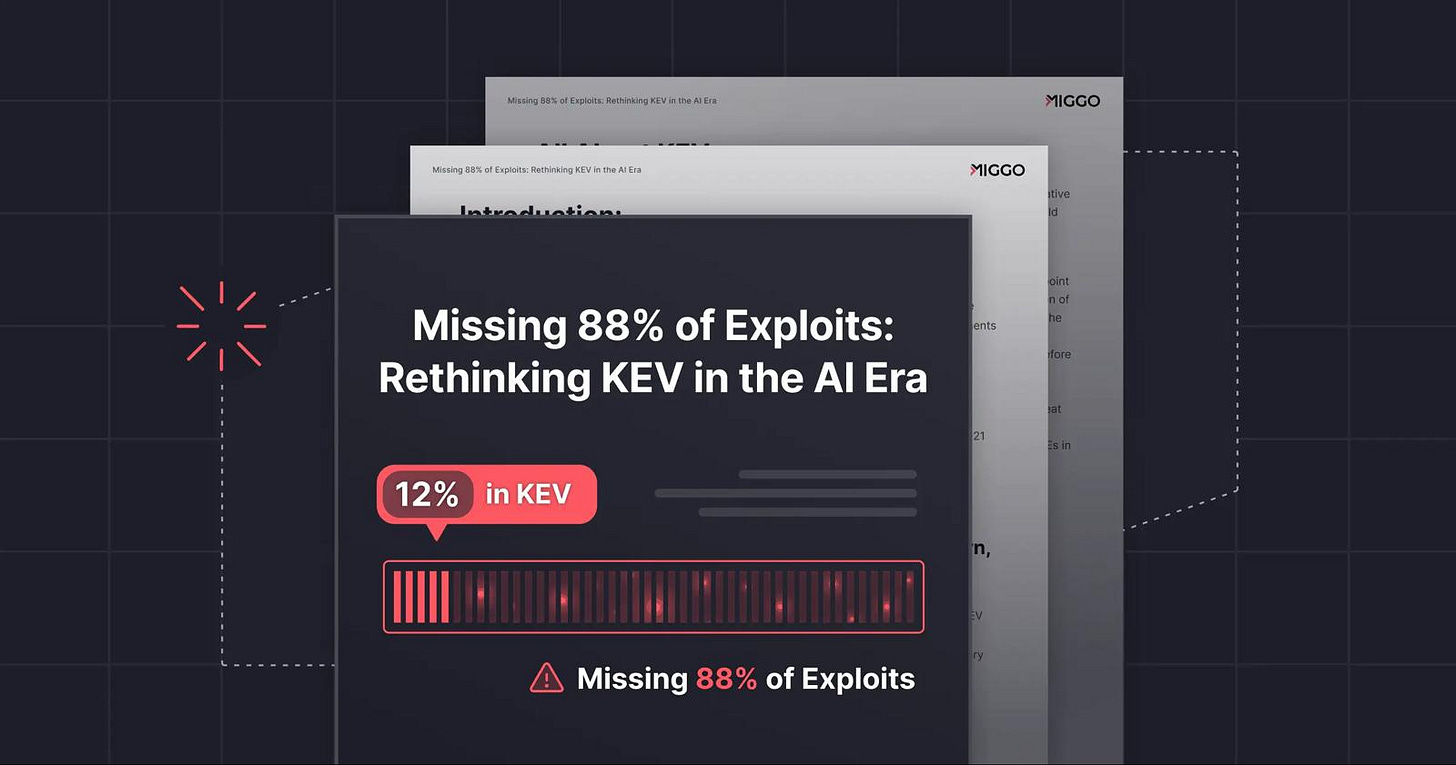

The comparison to KEV was jolting: Only 69 of the 572 vulnerabilities with known exploits appear in the KEV catalog. This data indicates that 88% of vulnerabilities with available exploits are not represented in KEV at all.

The disparity widened as Miggo dug deeper. Four hundred seven exploits were weaponized or fully functional, and 165 were proof-of-concept exploits. Yet, KEV contained only 68 of the 407 functional exploits, and just 1 of the 165 proof-of-concept exploits.

For defenders, the implication is unavoidable: most of the exploits that attackers could use today sit outside the system that was designed to help organizations identify what attackers are using.

The KEV list is not inaccurate; it is slow. It tracks confirmation. However, exploitation no longer waits for confirmation.

When AI Turns Every Disclosure Into a Live Threat

Miggo’s white paper notes a structural acceleration in the way attacks occur. In the past, attackers needed time to develop or adapt exploit code. Now, AI-assisted tooling allows exploitation within minutes of vulnerability disclosure, dramatically compressing the space between awareness and action.

The report builds this shift into a broader framework, particularly what Miggo calls the Four Vs of modern exploitation:

Volume: focusing on vulnerabilities that are actively exploitable in production, scaling automatically to thousands of new CVEs

Velocity: neutralizing attacks at execution from weeks to minutes, and reducing time to mitigation through AI-driven virtual patching

Variants: monitoring behavior rather than signature

Visibility: delivering continuous insight to turn blind spots into actionable intelligence

The upshot is simple: if defenders depend on KEV to know when exploitation starts, they are reacting after attacks have already become possible.

The New Definition of “Defense”: Time to Mitigation

Miggo doesn’t argue that KEV is wrong; only that KEV is now too slow to anchor cybersecurity programs. The company positions a replacement not in data sources but in where protection happens.

Instead of defending based on vulnerability listings, Miggo makes the case for proactive runtime defense. This model evaluates whether a vulnerability is exploitable inside the live application, then automatically deploys AI-generated virtual patching to neutralize the attack path in real time.

The white paper reports that runtime defenses can reduce time-to-mitigation from weeks or months to seconds, stopping exploit attempts even before a patch is available or a vulnerability is cataloged.

The logic shift is profound: Vulnerability knowledge becomes helpful, and exploit interruption becomes essential. Knowing is no longer enough; speed is now the differentiator.

What Success Looks Like in the Next Security Era

KEV has not failed. Instead, technology has simply outgrown the defensive model it supports. Exploitation has become faster than confirmation. The result is a protection gap that attackers exploit more effectively than ever.

Miggo’s research makes a pointed argument: security will no longer be defined by who knows about vulnerabilities, but by who can prevent exploitation first.

The future of cybersecurity will not be measured by how many CVEs an organization patches.

It will be measured by how little time attackers have before their attempts are blocked.

That 88% gap is alarming. The whole KEV reliance model seems to assume threats move slowly enough to catalog them, but as you pointed out, AI tooling has completly changed that timeline. If exploits are being weaponizd within minutes of disclosure, the idea of patching based on lagging lists feels less like a strategy and more like reactive damage control. The shift to runtime protection makes sense when you frame it around time to mitigation rather than just vuln counts.